Remembering Jimmy Carter and his Contribution to the Role of Psychoanalysis in World Affairs

Vamı k D. Volkan, M.D.

Abstract

In February 2023 98-year-old former President Jimmy Carter entered hospice care and began spending his remaining time at home with his family. This paper describes his personal, and The Carter Center’s financial, support for applying psychoanalytic approaches to understanding and calming large-group conflicts in Estonia and Albania and helping to enrich psychoanalytic knowledge of large-group psychology.

Keywords: large-group identity, Tree Model, mini-conflict, accordion phenomenon, transgenerational transmission, chosen trauma, chosen glory, undigested trauma, non-sameness, psychological border, time collapse, time expansion

The term large group describes hundreds, thousands, or millions of people—most of whom will never see or even know about each other as individuals—who share an identity. Revising Erik Erikson’s description of individual identity (Erikson, 1956), large-group identity expresses the subjective experience of thousands or millions of people who are linked by a persistent sense of sameness while also sharing some characteristics with others who belong to large foreign groups (Volkan, 1997). There are different kinds of large-group identities. The first type begins in childhood and is universal. It is the end-result of myths and realities of common beginnings, historical continuities, geographical realities, and other shared linguistic, societal, religious, and cultural elements. In everyday language, subjective experience of such large-group identities is expressed in terms such as “We are Catalan; we are Lithuanian Jews; we are French; we are Sunni Muslims; we are white supremacists in the United States.” Large-group identity also manifests in adults. Tens of thousands or millions of followers of a political party or employees of a huge international corporation can be imagined as belonging to this type of large group. However, followers of political parties or employees of corporations do not lose the large-group identity they developed in childhood. Religious cults such as Branch Davidians and terrorist organizations such as ISIS, on the other hand, do represent psychologically significant large groups that evolve during adulthood. Members of such organizations lose the superego-imposed restrictions and the moral attitudes they acquired as children. They become representatives of the large groups they join as adults and perceive their actions as duty, to protect or bring attention to their newly acquired large-group identity.

Psychoanalytic large-group psychology refers to making formulations about the conscious and unconscious shared past and present historical/social/religious/ psychological experiences that exist within a large group. Making such formulations enlarges our understanding of the emergence of present-day societal-political-religious-ideological events, leader-follower relationships, war-like situations and wars, allowing us to look at interactions between opposing large groups in depth. This is similar to a psychoanalyst making formulations about analysands’ developmental histories associated with various conscious and unconscious fantasies in order to understand what motivates certain behavior patterns, symptoms, and habitual interpersonal relationships.

Societal Conflicts, World Affairs and Psychoanalysis

In his early efforts to develop psychoanalytic theories, Freud ( 1905) minimized the idea of the sexual seduction of children coming from the external world in favor of it originating from the stimuli that come from the child’s own wishes and fantasies. Starting in 1925, the role of traumatic reality—actual sexual abuse—on individuals’ internal worlds became the basis of a long-lasting dispute between him and Sándor Ferenczi (Freud & Ferenczi, 1920–1933; Paláez, 2009). In 1932, Freud’s followers, encouraged by him, tried to block Ferenczi from delivering his “Confusion of Tongues” paper at the Wiesbaden International Psychoanalytic Conference, the paper that focused on the truthfulness of seduction and its lasting damaging impact for the developing child. In spite of the fierce opposition, Ferenczi ( 1933) delivered the paper, but then it was blacklisted by Jones from publication until 1949. During that same year Freud expressed pessimism about the role of psychoanalysis in wars or war-like situations in his correspondence with Albert Einstein (Freud, 1933). In 2006, I was the Fulbright-Sigmund Freud Privatstiftung Visiting Scholar of Psychoanalysis and had an office at 19 Berggasse in Vienna. While working in Freud’s house for four months I pictured him at this same location in 1932 and wondered about his response to Einstein. Anti-Semitism surrounded Freud at that time, and a year later Adolf Hitler would be the dictator of Germany. I wondered about Freud’s response to Einstein and thought that it reflected an attempt to deny the impending danger to himself, his family and neighbors (Volkan, 2013). Freud mentions war neurosis in his writings (for example, see Freud, 1926), but he discouraged his followers from considering major tragedies linked to war and politics within the psychoanalytic setting.

John Bowlby ( 1988) described that when he became an analyst in 1937, psychoanalysts in Great Britain were only interested in the internal worlds of their patients. At that time there was a saying that if the King died, psychoanalysts would not pay attention to it in their offices. Melanie Klein ( 1961) herself ignored the influences of war while treating one of her patients, a ten-year-old boy named Richard, whose analysis took place while World War II raged, literally overhead, during the London Blitz under which he and his analyst lived. In the 1960s when I was going through my training analysis, a deadly conflict between Cypriot Greeks and Cypriot Turks was taking place at my birthplace, the Mediterranean island Cyprus, and I was worried about the safety of my family members and friends. I came to the United States in early 1957, a few months after graduating from medical school in Turkey. My roommate for two years while I was attending medical school also was from Cyprus. He was killed on the island due to this conflict a few months after I came to the United States. While lying on my analyst’s couch there was no focus on the impact that events thousands of miles away had on me.

These attitudes also played a significant role in keeping psychoanalysts in their offices and discouraging open involvement in societal, educational, or political activities even though some decades earlier psychoanalysts such as Edward Glower ( 1947), Franco Fornari ( 1966), Robert Waelder ( 1971), Alexander Mitscherlich & Margarete Mitscherlich (Mitscherlich A., 1971; Mitscherlich & Mitscherlich, 1967) tried to open doors to such activities. It took some time to break the silence in the clinical setting that would free psychoanalysts to examine the Third Reich-related issues in their patients’ lives. We also know that German-speaking psychoanalysts had difficulties hearing Nazi-related influences in their German and Jewish patients (Grubrich-Simitis, 1979; Eckstaedt, 1989; Jokl, 1997; Streeck-Fischer, 1999; Volkan, Ast & Greer, 2002). One of the important contributors to breaking the silence was Judith Kestenberg ( 1982) who coined the term transposition, which described how survivor parents were transmitting their trauma unconsciously to their children. However, even in 2002, Ira Brenner who had studied and written a great deal about the impact of the Holocaust on affected individuals, stated how a number of “very talented ‘outsider’ analysts” challenged him by arguing that “analysis deals with the realm of psychic reality only” and that Brenner and his colleagues “were introducing an unnecessary element that only ‘muddied the waters’ and was unnecessary for successful treatment” (Brenner, 2002, p. xiii).

By the 1990s, even though these “outsider” analysts were still against including Holocaust-related psychological reactions in clinical work, there were already significant contributions by psychoanalysts illustrating the intertwining of internal and external worlds, both in individual psychological structures and societal situations. For example, in 1993 a group of psychoanalysts and psychoanalytically oriented psychiatrists formed a committee to study the psychodynamics of various aspects of international relationships. The group met twice a year for five years and engaged in dialogue, both among themselves and with many others in various disciplines, including historians, political scientists, and former diplomats. One aspect of international relationships that the group focused on was the psychodynamics of leaders and decision-making (Volkan et al., 1998). Michael Šebek ( 1994) studied societal responses to living under communism in Europe. Sudhir Kakar ( 1996) described the effects of Hindu-Muslim religious conflict in Hyderabad, India. Maurice Apprey ( 1993, 1998) focused on the influence of transgenerational transmission of trauma on African Americans and their culture. Nancy Hollander ( 1997) explored events in South America. Salman Akhtar ( 1999) wrote about immigration and identity.

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA) formed the Terror and Terrorism Study Group. Norwegian psychoanalyst Sverre Varvin chaired this group that lasted for several years (Varvin & Volkan, 2003). The IPA also established a committee in the United Nations and Vivian Pender became a spokesperson for psychoanalytic explanations of shared external world events. The theme of the 44 th Annual Meeting of the IPA in Rio de Janeiro in the summer of 2005 was Trauma, including trauma due to historical events. In 2011, during the plenary lecture at the American Psychoanalytic Association’s Winter Meeting, outgoing president Prudence Gourguechon urged the members of the association to show their faces in areas already in the public eye. She stated that if psychoanalysts do not attempt to explain the causality of disturbing events and provide professional information about human behavior, statements by others with less knowledge on such matters will prevail.

Now I will give examples of psychoanalytically studied and described societal and international events from the 2000s. Mitch Elliott, Kenneth Bishop and Paul Stokes ( 2004) and John Alderdice ( 2007, 2010) explored the situation in Northern Ireland. Nancy Hollander ( 2010) examined the impact of September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States. Gerard Fromm ( 2011) edited a book on transmissions of the influence of trauma from generation to generation, and later wrote more about this topic as well as about radicalization, war trauma and cultural healing (Fromm, 2022). Tomas Böhm and Suzanne Kaplan ( 2011) focused on revenge and reconciliation. Schmuel Erlich ( 2013) explored the terrorist mind. Edward Shapiro ( 2019) described the journey from being an individual to joining society as a citizen and examined autocratic leaders and societal divisions. Stuart Twemlow and his colleagues worked in the “trenches” (Sklarew, Twemlow & Wilkinson, 2014) and focused on creating a peaceful learning environment for children that prevents bullying in schools and decreases prejudice, violence, and incest in communities (Mahfouz, Twemlow & Scharff, 2007; Twemlow & Sacco, 2011). The coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and the availability of technical online communication changed psychoanalytic practice, while psychoanalysts became more aware of the intertwining of shared external events and responses from the human psyche (Bakó & Zana, 2023; Volkan, 2021a). The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2002 also sparked an examination of individual and large-group psychology concerning this new, horrible event (Ihanus, 2022; Volkan & Javakhishvili, 2022).

The Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction and The Carter Center

In 1977, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat went to Israel and at the Knesset he referred to a psychological wall between the Israelis and the Arabs—a wall that, he stated, accounted for 70 percent of the problems between them. In response, the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Psychiatry and Foreign Affairs, of which I was a member, brought influential Arabs and Israelis together for unofficial dialogues once or twice per year for six years to find out if this wall could be made permeable. This experience was the catalyst for a career that took me beyond the psychoanalytic couch. In 1987 I founded the Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction (CSMHI) at the School of Medicine, University of Virginia. My aim was to study large-group tensions, racism, terrorism, transgenerational transmissions of trauma and leader-follower relationships. Because no single discipline can fully illuminate such deep-seated and complex issues, CSMHI’s faculty and board included experts in psychoanalysis, psychiatry, psychology, diplomacy, history, political science, and environmental policy. I felt that their combined perspectives and experience would provide in-depth analyses of political, historical, and social issues and the psychological processes that invariably exist beneath their surfaces.

Most likely, CSMHI would have remained a place to discuss political psychology intellectually in depth. But our signing an official contract with the Soviet Duma to start a dialogue series aimed at helping the Soviet and the American people get to know one another better and offer ideas for improving Soviet-American relations gave us an opportunity to begin to work in many trouble spots in the world. In my paper “Remembering Gorbachev” published in this journal (Volkan, 2022) I tell the story of how signing this contract was made possible. CSMHI had projects in the Baltic Republics, Kuwait, Albania, former Yugoslavia, Georgia, South Ossetia, Turkey, Greece, and elsewhere. CSMHI’s journal, Mind & Human Interaction examined the relationship between psychoanalysis and history, political science and other fields. CSMHI received financial support from many foundations, but it was our collaboration with The Carter Center that played the crucial role in our developing a psychoanalytically informed approach to international conflicts and initiating activities to support and maintain peaceful co-existence for opposing large groups (Volkan, 1988, 1997, 1999a, 1999b, 2004, 2006, 2013, 2020). CSMHI was closed and its journal’s publication came to an end in 2004, two years after my retirement.

After his defeat in the 1980 presidential election, former United States President Jimmy Carter and former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, in partnership with Emory University, founded the Atlanta-based Carter Center in 1982. The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization. Its aim is to advance human rights and alleviate unnecessary human suffering with programs that work toward advancing international peace, fighting diseases, and building hope. In 1987 The Carter Center established the International Negotiation Network (INN) under the umbrella of The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program (CRP). Through INN, CRP would coordinate third-party assistance, expert analysis and advice, workshops, media attention, and other means to facilitate constructive prevention or resolution of international conflicts. During the year INN was established there were 111 armed conflicts in the world and only 10 percent of them could be addressed by international agencies. The rest of these conflicts were considered domestic struggles, such as severe societal divisions and civil wars, which did not fall within the jurisdiction of organizations like the UN. The purpose of INN was to fill this mediation gap.

In the late 1980s, while giving a talk at a meeting organized by United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC, I met Dayle Powell (later Dayle Spencer), who had been a trial lawyer for 10 years before becoming a fellow in 1985, and then Director of The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program (CRP). She asked me to be a consultant to the INN Council. I accepted and went to Atlanta, where, for the first time, I met Jimmy Carter, Rosalynn Carter and about a dozen other INN council members. These included the former president of Nigeria, General Olusegun Obasanjo; the widow of assassinated Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, Lisbeth Palme, who was a member of the Swedish Committee for UNICEF (later UNICEF’s Chairperson) and a child psychologist. I also met Nobel Peace Prize winners Oscar Arias Sánchez, Elie Wiesel, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. President Carter had also received a Nobel Peace Prize in 1982. I already knew a few members of the INN council: Harold Saunders, a former Assistant Secretary of State who was a Board member of CSMHI, Eileen Babbitt from Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University; Kevin Clements and Christopher Mitchell from George Mason University; and Ambassador Tahseen Basher from Egypt who had participated in the meetings organized by the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on Psychiatry and Foreign Affairs. (A complete list of INN members is noted in my book, Enemies on The Couch [Volkan, 2013]). A year later I had the honor to become a member of the INN and its only psychoanalyst. I began going to The Carter Center annually to lecture large international audiences and/or to participate in smaller gatherings for the purpose of finding peaceful solutions to specific large-group problems.

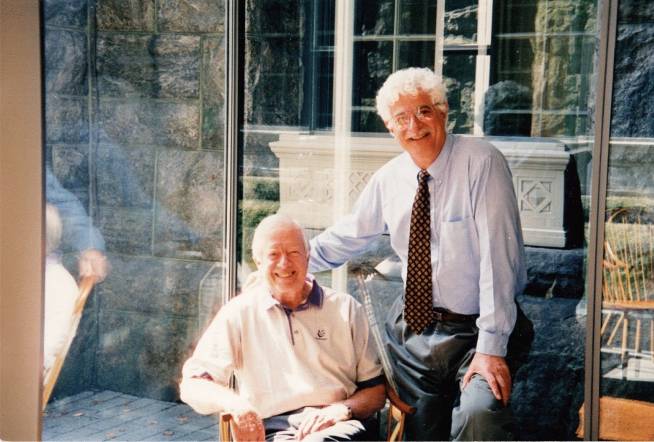

Getting to Know Jimmy Carter

My first impression of President Carter was that he was highly intelligent, in possession of unshaken idealism, and was deeply committed to bettering the world. I observed that he and Rosalynn were very close, an almost inseparable couple, doing most of their thinking and activities together. While in Atlanta INN members had lunch with the Carters and when the group was large enough to require two tables, they would each preside over one. Some INN members and sometimes other guests, especially those from foreign countries, would rush to sit at the former president’s table. Because of this, most of the time I often I sat at Rosalynn Carter’s table. Her intense interest in mental health directed many of our conversations. I also appreciated the opportunity to talk with Desmond Tutu whenever he was in Atlanta. I realize now that he was preparing to assemble the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1995–1998) at this time and showed great interest in the psychology of individual and societal traumas and the necessity of individual and societal mourning in helping to decrease their impact (Volkan, 2009).

My personal association with Jimmy Carter began when he asked me to lead a workshop dealing with the Cyprus problem. Twenty-three people—high-level Cypriot Greek and Cypriot Turkish politicians as well as the Turkish representative to the United Nations in Geneva—would be attending this workshop. I was reluctant since I thought that I might not be able to maintain my neutrality. I began to meet with Carter privately. I learned that he wanted to observe a meeting directed by a psychoanalytically informed person instead of watching another meeting where the facilitator would help the opposing parties bargain. He told me that he was an engineer and was accustomed to getting results by pushing a button. But he was also very much aware of psychological aspects of negotiations. He described to me how he worked with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at the Camp David retreat in Frederick County, Maryland in 1978 and how important an understanding of human emotions had been during the intense negotiations of the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, which he described in his book, Keeping Faith (Carter, 1982).

During the last day at Camp David, Prime Minister Begin adamantly refused to sign any accord. Nonetheless, photographs were taken of the leaders together, and Begin asked to have three signed by his colleagues that he could give to his grandchildren. President Sadat had already autographed the pictures, and President Carter, after obtaining the names of Begin’s grandchildren, personalized his own inscriptions. Afterward, Carter went to Begin’s cabin with the signed photographs. When Begin saw a photograph with his granddaughter’s name on it, tears welled up in his eyes and he began talking about his grandchildren. Carter described “a love fest” between Begin and Sadat after this incident. The Camp David accords were signed.

After my talks with Jimmy Carter, I conducted the Cyprus workshop that he attended. Although Jimmy Carter offered to go to the island and help both sides of the conflict negotiate a peaceful solution, neither side invited him.

I got to know Jimmy Carter well when I was invited to join him and his wife, Rosalynn, in Senegal in September 1992. About a dozen of us stayed in a Dakar hotel, which had been built (or paid for) a year earlier by King Fahd of Saudi Arabia for a meeting of the Islamic Conference. For security reasons there were no individuals in the entire hotel besides The Carter Center people and the security staff for the duration of our gathering. While in Senegal, I observed Carter holding a meeting with representatives of different African regions who were presenting papers filled with statistics, charts, graphs and somewhat mechanistic ways of ending conflicts. I thought, “who are we now?” and that border issues could not be handled as easily as statistical charts and mechanical measures suggested.

Landing Savané—whose wife, Marie Angelique had been the director of the UN’s African Division and was an INN member—was running against the current president of Senegal at that time. Carter, and those who went to Dakar with him, became involved in this man’s campaign while visiting and experienced huge crowds dressed in wonderful, colorful native dress, chanting and dancing, greeting him wherever he went.

In the evenings we would gather around the hotel’s big swimming pool, which was filled with hundreds and hundreds of croaking frogs, a setting that allowed the former US president and the rest of us to relax, tell jokes, and take a break from the seriousness of Africa’s deadly large-group issues. This experience allowed me to get to know Jimmy Carter closely and appreciate further his emotional dedication to bring about a better world. I sensed that he had deep religious beliefs. His spiritual convictions most likely played a role in his personal thinking, activities, and motivation to become a leader (see: Carter, 1996), but in his conversations with the rest of us he never used religion to justify his political thinking. I am also reminded that he never invoked religion to justify his politics, nor did he ever discuss the loss of his second presidential term, though Rosalynn would occasionally refer to it.

One evening in Senegal Jimmy and Rosalynn left our gathering by the frog-filled swimming pool early. The next day I heard that they had taken a small plane to Liberia with Dayle Spencer—to an area where factions were engaged in a violent and deadly struggle—so that they could try and convince these enemies to end the bloodshed.

Dr. Joyce Neu, a linguist and the assistant Director of The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program, was in Senegal with us. I had met her earlier but had never had the opportunity to work with her. I learned that she was a Peace Corps volunteer in Senegal from 1972 to 1974. While the Carters and Dayle Spencer were away Joyce, the other INN member in Senegal, Lisbet Palme, and I drove around the country for two days, visiting private homes and learning, with Joyce Neu’s help, something about Senegalese culture. During these two days I worried about the former president, his wife and Dayle Spencer’s safety. I recall having a visual fantasy of a small airplane landing on a river and Jimmy Carter coming out of the airplane to step in a little boat while bullets from both sides of the river zoomed above his head. It was a relief to finally hear from them. Once again, I appreciated the former president’s personality—one that led him to commit to building a better world.

The Development and Application of the Tree Model in Estonia

After the collapse of the Soviet Union some CSMHI colleagues and I visited Lithuania and Latvia to try and help. The Baltic Republic states, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia, were the first national republics to declare independence and achieve a peaceful divorce from the Soviet Union. We brought together influential representatives from the now independent Baltic Republics and Soviet Union (and later from the Russian Federation). The main issue was the large number of Russians who still lived in the Baltic Republics. Starting in April 1994 CSMHI and The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program (CRP) started a joint project and began to work in Estonia, where one-third of its 1.5 million inhabitants were Russians and other Russian speakers (Russian or Russian-speaking citizens and non-citizens from other locations in the former Soviet Union who were not Russians). In addition, Estonia was facing a border adjustment issue. Estonians believed that a strip of land in the Russian territory along the border belonged to them.

Within the CSMHI/CRP interdisciplinary facilitating team of the Estonia project Joyce Neu represented The Carter Center, while Harold Saunders and I represented both The Carter Center and CSMHI. When we landed at the Tallinn Airport for the first time in April 1994, the airport building was dysfunctional. The immigration and customs officers did not have offices, only two long tables in front of the airport building’s door facing the runways. This was our first indication that this was indeed a traumatized country.

The CSMHI/CRP interdisciplinary facilitating team, after visiting different parts of Estonia and interviewing many people, began to bring together the same selected influential individuals— for four days of dialogue. We had chosen ten Estonians, eight Russian speakers in Estonia and eight Russians from Russia. To help them find peaceful solutions to their large-group problems and to maintain peace between Estonia and Russia, we held a total of 44 days of dialogue between 1994 and 1996 (twice in 1994 and 1996 and seven times in 1995). We called this psychoanalytically informed methodology the Tree Model and it incorporates three phases, about which I have written extensively (Volkan, 1999a, 2006, 2013, 2020).

Phase I – Psychopolitical Assessment of the Situation (Representing the Roots of a Tree)

This phase of the Tree Model includes in-depth psychoanalytically-informed interviews with a wide range of people who represent the large groups involved, through which an understanding begins to emerge concerning the main aspects, including unconscious ones that surround the situation that needs to be addressed.

Every conflict has its hot locations. These may include national cemeteries, memorials to those who have died in large-group conflicts, and other historically important or symbolic locales. Visiting such places with members of the large groups in conflict allows the facilitating team to quickly get to the heart of what these sites represent and why they are perceived as hot in the context of the conflict. One of the hot places in Estonia was the former Soviet nuclear submarine base at Paldiski. What we found was that Estonians suffered from an underlying anxiety of “disappearing” as an ethnic group, of ceasing to exist. With the exception of a brief period of independence between 1918 and 1940, Estonians have lived for a millennium under the domination of others. When at last they regained their independence in 1991, they remained anxious that they would once again be swallowed up by a neighboring group (Russians, in this case). Estonians’ anxiety over foreign domination was also fueled by the fact that every third resident of Estonia was ethnic Russian or a Russian-speaker.

While there were plenty of real-world issues to attend to, the perception that Estonia would disappear caused resistance to policies for integrating non-Estonian residents. If Estonian and Russian “blood” were to “mix,” the uniqueness of the Estonian people—whose sense of identity had managed to persist despite their small numbers and adverse conditions over the centuries—might not survive. Our diagnosis then indicated the need to help Estonians differentiate real issues from fantasized fears so they could deal more adaptively with the integration of the Russian-speakers living in Estonia. In summary, during this assessment phase, the team examines how elements of a large group’s identity are heightened when the large group is threatened and under stress. This preoccupation colors every aspect of the conflict and the relationship with the opposing large group.

Phase 2 – Psychopolitical Dialogues Between Influential Members of Opposing Groups (representing the trunk of a tree)

Psychopolitical dialogues between influential representatives of opposing large groups are conducted under the guidance of a psychoanalytically informed facilitating team and take place in a series of multi-day meetings, as often as possible, over several years. As I stated above, psychopolitical dialogues in Estonia lasted throughout three years. Keeping in mind the clinical psychoanalytic technique, during our first meeting my facilitating team and I told Estonians, Russian speakers and Russian participants that we would not give them advice; they would find their own solutions, and we suggested that they report whatever came to mind. As these dialogues progressed, we learned about various shared real as well as fantasized psychological ways large groups hold on to their large-group identities. When brought to the surface and articulated, fantasized threats to large-group identity were interpreted and realistic communication could take place.

Our conducting psychopolitical dialogues in Estonia helped me to notice some existing psychoanalytic concepts related to dealing with large-group conflicts and psychoanalytic large-group psychology. I also developed some new concepts. I named one mini conflict. At the outset of a dialogue meeting, a disruptive situation evolves abruptly— such as a participant losing a return airplane ticket while knowing it would be needed to fly back home at the meeting’s conclusion. This development absorbs the attention and energy of all participants. Such a situation is usually marked with a sense of urgency, yet the content of this crisis is essentially insignificant in comparison to the salient aspects of the ethnic or national conflict for which the dialogue meeting has been organized. Mini conflict is used as resistance to communicate with the enemy.

I also came up with two other concepts which I named chosen glory and chosen trauma. A chosen glory refers to historical tales of grandeur, past victories in battle and other great accomplishments of a technical or artistic nature which are used to bolster large-group identity. A chosen trauma is the shared mental representation of an event in a large group’s history during which the group suffered a catastrophic loss, humiliation, and helplessness at the hands of enemies. When members of a victim group are unable to mourn such losses and reverse their humiliation and helplessness, they pass on to their offspring the images of their injured selves and psychological tasks that need to be completed. This process is known as the “transgenerational transmission of trauma” (see Volkan, 2021b). All such images and tasks that are handed down contain references to the same historical event, and as decades and centuries pass, the mental representation of this event links all the individuals in the large group. Thus, the event’s mental representation emerges as a very significant large-group identity marker. The Russians’ chosen trauma referred to their suffering at the hands of Tatars and Mongols in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. During the dialogue series, the Russian delegates suddenly would start talking about the Tatar-Mongol invasion whenever they noticed how Estonians felt angry at Russians as their occupiers. The idea behind this was to state that Russians themselves were occupied by Others who had done bad things and that Russians were good occupiers of Estonia by taking care of Estonians. When a chosen trauma is activated, a time collapse takes place. Perceptions and feelings related to a past event centuries ago become fused to the reactions and emotion connected with a present event.

The term chosen trauma does not apply to fairly recent shared traumas (“undigested traumas”) at the hands of others that still induce intensely personal feelings in people. For example, the Holocaust is not a chosen trauma; it is an “undigested trauma.” Descendants still have pictures and belongings from survivors; survivors’ stories are still alive. Because the Jewish people were the victims of the Holocaust, this horrible historical event is a marker of their shared identity.

I named another concept the accordion phenomenon. When more empathic communication begins in the dialogue series, the participants of the opposing large groups experience a rapprochement. This closeness is then followed by a sudden withdrawal from one another and then again by closeness. The pattern repeats numerous times. I liken this to the playing of an accordion—squeezing together and then pulling apart. Initial distancing is a defensive maneuver to keep aggressive attitudes and feelings in check, since, if the opponents were to come together, they might harm one another—in fantasy—or in turn become targets of retaliation. When opposing teams are confined together in one room, sharing conscious efforts for peace, sometimes they must deny their aggressive feelings as they press together in a kind of illusory union. When this becomes oppressive, it feels dangerous, and distancing occurs again. The most realistic discussions take place after the facilitating team has allowed the accordion to play for a while, until the squeezing and distancing become less extreme.

During the dialogue series, I noted patterns reminding me of Melanie Klein’s ( 1946), projective identification that psychoanalysts see in individual patients. During the psychopolitical dialogues one team may project onto the other their own wishes for how the opposing side should think, feel, or behave. The first team then identifies with the Other that houses their projections—this Other is perceived as actually acting in accordance with the expectations of the former. In effect, one team becomes the spokesperson for the other team, and since this process takes place unconsciously, the first team actually believes their remarks about the enemy. However, the resulting relationship is not real since it is based on the processes of only one party. (The CSMHI/CRP interdisciplinary facilitating team interpreted or interfered with the development of projective identification.)

I call another concept the maintenance of non-sameness. Much earlier Freud ( 1921), noted minor differences among neighboring large groups, but considered these differences as harmless. Usually large groups in conflict have major noticeable differences, such as language, religion, sometimes skin color and so on. I noted that minor differences between antagonists can become major problems. When there is a conflict between two large groups, any signal of similarity is perceived, often unconsciously, as unacceptable; minor differences therefore become elevated to great importance to protect non-sameness. This leads to turning physical borders between large groups into psychological borders. CSMHI members and I have found that minor differences between opposing groups are often psychologically harder to deal with than major differences, such as language or religion. When minor differences become resistances, the facilitating team tries to enhance and verify each group’s identity, so that the minor differences remain minor.

I call my next concept symbolizing the conflict and “playing” with it. A symbol or metaphor that represents important aspects of the conflict emerges from within the dialogue. When our dialogue series progressed, Estonians called their large group a mouse while referring to the stronger enemy, the Russians, as an elephant. They asked how a mouse can protect itself when it is next to an elephant. They started to play with this question, for hours, for days. Poisonous emotions began to disappear, and laughter often accompanied this play. Realistic discussion of issues could then ensue. (It is important to note that the facilitating team should not introduce or fabricate a metaphor or “toy” for the participants to play with—it must be created or provided by the participants themselves.)

My last concept is time expansion. As noted earlier, when chosen traumas (as well as undigested traumas) are reactivated, the emotions and perceptions pertaining to them are felt as if the past trauma occurred recently—they become fused with emotions and perceptions pertaining to the present and are even projected into the future. Understandably, this time collapse complicates attempts to resolve the conflicts at hand. To counteract this phenomenon and to encourage a time expansion, facilitators must allow discussions to take place concerning the chosen trauma or the undigested trauma itself and participants’ personal traumas pertaining to the large-group conflict and their experience of mourning. From a clinical point of view, human beings must mourn when they give up something important or when they lose a stubbornly held position. Mourning in this sense does not refer to observable behavior such as crying, but to psychodynamic processes that occur after loss. If feelings and issues about the past can be distanced and separated from present problems, then today’s problems can be more realistically discussed.

Phase 3 – Institution Building (representing the branches of the tree)

The third component of the Tree Model involves transferring the insights from the dialogues into concrete actions affecting the societies involved. In collaboration with the dialogue participants and local contacts trained in the CSMHI methodology, the CSMHI team seeks to prevent stagnation or slippage backwards by institutionalizing the progress that has been made. The local contact group includes clinicians whom we trained to work in the societies involved at the grass-roots level to create models for coexistence or collaboration.

In Estonia, for example, within three years following the psychopolitical dialogues, we were able to build model coexistence projects in two villages where the population is half Estonian and half Russian. The most important task here was to teach people at the grass-roots level to gain political power and to help local contact groups to evolve as effective NGOs. We also created a model to promote integration among Estonian and Russian schoolchildren and influenced the language examination required for Russians to become Estonian citizens. Joyce Neu from The Carter Center, as a linguist, contributed to this project greatly.

There are limitations to The Tree Model. First, it requires that psychoanalysts and other clinicians develop expertise in international relations and collaborate with diplomats, political scientists, and historians. Building an interdisciplinary team has its own psychodynamic challenges. Second, the tree needs water (funds), and it can be difficult to find sponsors for a process that will take many years before the fruits of the tree can be observed by everyone. Nevertheless, as the world changes, there is an increasing need to find serious new methods for preventing conflicts and reducing tensions between opposing large groups. The Tree Model is offered as a methodology for a new type of preventive or corrective diplomacy carried out systematically by a neutral third party.

It is clear that without Jimmy Carter’s willingness to help my colleagues and me, a psychoanalytically informed methodology which, in its various forms would be useful dealing with large-group conflicts and problems, could not have been developed. Our meetings in Estonia, during the second phase of The Tree Model, were funded by a $1 million grant made to The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program by the Charles Mott Foundation. I also want to report that a member of the Estonian team, Arnold Rüütel, became the President of Estonia from October 8, 2001 to October 9, 2006. One project of our third phase of The Tree Model is the focus of a classic documentary called The Dragon’s Egg (King, 1999) by the late well-known documentary filmmaker Allan King. (On November 5, 2022 at the Applied Psychoanalysis Programme of the Toronto Psychoanalytic Society, The Dragon’s Egg was screened and discussed.)

Visits to Albania

In 1998 The Carter Center asked me to carry out a project in Albania, a country about the size of Massachusetts, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. This project would be funded by The Carter Center. It is beyond the aim of this paper to give a detailed history of Albania, but briefly, in 1920, this country became a member of the League of Nations. From 1944 Albania found itself under the leadership of communist Enver Hoxha whose extreme totalitarian rule lasted until his death in April 1985. The first free elections in Albania since the mid-1920s took place in December 1989. But communism, under a different name, continued. In March 1992, the Albanian Democratic Party led by a young cardiologist-turned politician, Sali Berisha, swept a convincing electoral victory. During his time in power, US President Jimmy Carter visited Albania, and he continued his interest in that country, hoping democracy would develop there.

In 1998 I joined Joyce Neu and the late historian Norman Itzkowitz from Princeton University and member of CSMHI on a trip to Albania to investigate the legacy of Enver Hoxha’s totalitarian rule and to find ways to stabilize democracy there. I conducted lengthy psychoanalytic interviews with several Albanians and learned a great deal about the impact of a totalitarian regime on the human psyche. Healing the societal split between those who were associated with the torturers during the Enver Hoxha period and those who were related to the torture victims would be the main focus of our project. We could not return to Albania in 1999 because such a visit would have been too dangerous, as there were reports that Osama bin Laden was planning terrorist attacks in that region. My second visit to Albania took place in 2000. (I wrote in detail about our work in Albania in my book, Blind Trust: Large Groups and Their Leaders in Times of Crises and Terror [Volkan, 2004]). In the end, The Carter Center would not start a multi-year project in Albania like the one that was carried out in Estonia.

Last Words

In 2001 Joyce Neu left The Carter Center and went San Diego, California to be the Founding Director of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice, which was established in 2000 at the University of San Diego. Earlier, Dayle Spencer and her husband Mark Spencer had moved to Hawaii. The Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution program, as I had experienced it, came to an end. The last time I saw Jimmy Carter was during a Dedicatory Conference for the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice in 2001. Both of us attended this event to wish Joyce Neu success and happiness in her new position.

This paper does not intend to examine the life of former President Jimmy Carter and come up with ideas about why he became an advocate for the wellbeing of people worldwide. I did not intend this paper to be a psychobiography. He has written many books, including one which contains his poems (Carter, 1995) and given me signed copies of six of his books. As I have read them, I sensed that he, himself, wondered why he developed a personality with high expectations and wishes for the world’s well-being. This paper is simply my way of remembering Jimmy Carter while also informing my colleagues, friends and readers that his support for viewing world affairs through a psychoanalytic angle has been very much appreciated.

Notes

- Vamık D. Volkan, MD is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry, University of Virginia; Training and Supervising Analyst Emeritus, Washington Baltimore Center for Psychoanalysis; Senior Erikson Scholar-Emeritus, Erikson Institute for Education, Research, and Advocacy of the Austen Riggs Center; President Emeritus of International Dialogue Initiative and Past President of Virginia Psychoanalytic Society, Turkish-American Neuropsychiatric Society, International Society of Political Psychology, and American College of Psychoanalysts.

- Dr. Volkan is the author, coauthor, editor or coeditor of over sixty psychoanalytic and psychopolitical books, some of which has been translated into Turkish, German, Russian, Spanish, Japanese, Greek and Finnish. He has written hundreds of published papers and book chapters. He has served on the editorial boards of sixteen national or international professional journals, including the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Dr. Volkan was the Guest Editor of the Diamond Jubilee Special Issue of the American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 2015. He has also received numerous awards and honors for his work on the application of psychoanalytic thinking between countries and cultures, individual and societal mourning, transgenerational transmissions of trauma and the therapeutic approach to primitive mental states.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akhtar S. Immigration and identity: Turmoil, treatment and transformation. London: Karnac; 1999. [ Google Scholar]

- Alderdice J. The individual, the group and the psychology of terrorism. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19:201–209. doi: 10.1080/09540260701346825. [ DOI] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Alderdice J. Off the couch and round the conference table. In: Lemma A, Patrick M, editors. Contemporary psychoanalytic applications. New York and London: Routledge; 2010. pp. 15–32. [ Google Scholar]

- Apprey M. The African-American experience: Forced immigration and transgenerational trauma. Mind and Human Interaction. 1993;4:70–75. [ Google Scholar]

- Apprey M. Reinventing the self in the face of received transgenerational hatred in the African American community. Mind and Human Interaction. 1998;9:30–37. [ Google Scholar]

- Bakó T, Zana K. Psychoanalysis, COVID and mass trauma: The trauma of reality. New York: Routledge; 2023. [ Google Scholar]

- Böhm T, Kaplan S. Revenge: On the dynamics of a frightening urge and its taming. London: Karnac; 2011. [ Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [ Google Scholar]

- Brenner, I. (2002). Foreword. In The Third Reich in the unconscious: Transgenerational transmission and its consequences. V. D. Volkan, G. Ast, & W. Greer (Eds.). (pp. xi–xvii). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

- Carter J. Keeping faith. Memoirs of a president. New York: Bantam Books; 1982. [ Google Scholar]

- Carter J. Always a reckoning and other poems. New York: Times Books; 1995. [ Google Scholar]

- Carter J. Living faith. New York: Times Books; 1996. [ Google Scholar]

- Eckstaedt, A. (1989). Nationalsozialismus in der “zweiten Generation”: Psychoanalyse von Hörigkeitsverhältnissen [National Socialism in the second generation: Psychoanalysis of master-slave relationships]. Frankfurt A. M.: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Elliott M, Bishop K, Stokes P. Societal PTSD? Historic shock in Northern Ireland. Psychotherapy and Politics International. 2004;2:1–16. doi: 10.1002/ppi.66. [ DOI] [ Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. The problem of ego identification. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 1956;4:56–121. doi: 10.1177/000306515600400104. [ DOI] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Erlich HS. The couch in the marketplace: Psychoanalysis and social reality. London: Karnac; 2013. [ Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi, S. (1933). Confusion of tongues between adults and the child. The language of tenderness and of passion. In Final contribution to the problems and methods of psychoanalysis. (pp. 156–167). London: Karnac Books. 1994. Also in International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 30, 225–230. 1949.

- Fornari, F. (1966). The psychoanalysis of war. A. Pfeifer (Trans.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1975.

- Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition, Vol. 7, (pp. 135–243). London: Hogarth.

- Freud, S. (1921). Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. Standard Edition, Vol.18, (pp. 65–143). London: Hogarth.

- Freud, S. (1926). The question of lay analysis. Standard Edition, Vol. 20, (pp. 179–258). London: Hogarth.

- Freud, S. (1933). Why War? (Co-authored with Albert Einstein). Standard Edition, Vol. 22, (pp. 197–215). London: Hogarth.

- Freud, S. & Ferenczi, S. (1920–1933). The correspondence for Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 3, 1920–1933. E. Falzeder & E. Brabant (Eds.), with the collaboration of P. Giampieri-Deutsch under the supervision of A. Haynal. P. T. Hoffer (Trans.). With an Introduction by J. Dupont. Cambridge, MA/London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2000.

- Fromm MG, editor. Lost in transmission: Studies of trauma across generations. London: Karnac; 2011. [ Google Scholar]

- Fromm MG. Traveling through time: How trauma plays itself out in families, organizations and society. UK: Phoenix; 2022. [ Google Scholar]

- Glower E. War, sadism, and pacifism: Further essays on group psychology and war. London: Allen and Unwin; 1947. [ Google Scholar]

- Grubrich-Simitis I. Extremtraumatisierung als kumulatives Trauma: Psychoanalytische Studien über seelische Nachwirkungen der Konzentrationslagerhaft bei Űberlebenden und ihren Kindern [Extreme traumatization as a cumulative trauma: Psychoanalytic studies on the mental effects of imprisonment in concentration camps on survivors and their children] Psyche. 1979;33:991–1023. [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Hollander NC. Love in a time of hate: Liberation psychology in Latin America. New York: Other Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar]

- Hollander NC. Uprooted minds: Surviving the political terror in the Americas. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. [ Google Scholar]

- Ihanus J. Putin, Ukraine and fratricide. Clio’s Psyche. 2022;23(3):300–311. [ Google Scholar]

- Jokl, A. M. (1997). Zwei Fälle zum Thema “Bewältigung der Vergangenheit” [Two cases referring to the theme of “mastering the past”]. Frankfurt A. M.: Jüdischer Verlag.

- Kakar S. The colors of violence: Cultural identities, religion, and conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar]

- Kestenberg JS. A psychological assessment based on analysis of a survivor’s child. In: Bergman MS, Jucovy ME, editors. Generations of the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press; 1982. pp. 158–177. [ Google Scholar]

- King, A. (1999). The dragon’s egg: Making peace on the wreckage of the twentieth century. [Documentary film]. Vancouver, BC: Allan King Associates.

- Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 27, 99–110. [ PubMed]

- Klein, M. (1961). Narrative of a child analysis: The conduct of the psychoanalysis of children as seen in the treatment of a ten-year-old boy. London: Hogarth Press.

- Mahfouz, A., Twemlow, S. & Scharff, D. E. (2007). The future of prejudice: Psychoanalysis and the prevention of prejudice. New York: Jason Aronson.

- Mitscherlich A. Psychoanalysis and aggression of large groups. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1971;52:161–167. [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Mitscherlich, A. & Mitscherlich, M. (1967). The inability to mourn: Principles of collective behavior. B. R. Placzek (Trans.). New York: Grove Press. 1975.

- Paláez MG. Trauma theory in Sándor Ferenczi’s writings, 1931–1932. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2009;90:1217–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-8315.2009.00190.x. [ DOI] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Śebek M. Psychopathology of everyday life in the post-totalitarian society. Mind and Human Interaction. 1994;5:104–109. [ Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E. R. (2019). Finding a place to stand: Developing self-reflective institutions, leaders and citizens. Oxfordshire: Phoenix.

- Sklarew, B., Twemlow, S. W. & Wilkinson, S. M. (Eds.). (2014). Analysts in the trenches: streets, schools, war zones. New York: Routledge.

- Streeck-Fischer A. Naziskins in Germany: How traumatization deals with the past. Mind and Human Interaction. 1999;10:84–97. [ Google Scholar]

- Twemlow SW, Sacco FC. Preventing bullying and school violence. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publication; 2011. [ Google Scholar]

- Varvin S, Volkan VD, editors. Violence or dialogue: Psychoanalytic insights on terror and terrorism. London: International Psychoanalytical Association; 2003. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. The need to have enemies and allies: From clinical practice to international relationships. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1988. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Bloodlines: From ethnic pride to ethnic terrorism. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1997. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. The Tree Model: A comprehensive psychopolitical approach to unofficial diplomacy and the reduction of ethnic tension. Mind and Human Interaction. 1999;10:142–210. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Das Versagen der Diplomatie: Zur Psychoanalyse Nationaler, Ethnischer und Religiöser Konflikte [The Failure of Diplomacy: The Psychoanalysis of National, Ethnic and Religious Conflicts] Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag; 1999. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Blind trust: Large groups and their leaders in times of crisis and terror. Charlottesville, VA: Pitchstone Publishing; 2004. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Killing in the name of identity: A study of bloody conflicts. Charlottesville, VA: Pitchstone Publishing; 2006. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan, V. D. (2009). The next chapter: Consequences of societal trauma. In Memory, narrative and forgiveness: Perspectives of the unfinished journeys of the past. P. Gobodo-Madikizela & C. van der Merwe (Eds.). (pp. 1–26). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Volkan VD. Enemies on the couch: A psychopolitical journey through war and peace. Durham, NC: Pitchstone; 2013. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Large-group psychology: Racism, societal divisions, narcissistic leaders and who we are now. London: Phoenix Publishing; 2020. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Sixteen analysands’ and large groups’ reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 2021;18:159–168. doi: 10.1002/aps.1696. [ DOI] [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Trauma, prejudice, large-group identity and psychoanalysis. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2021;81:137–154. doi: 10.1057/s11231-021-09285-z. [ DOI] [ PMC free article] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD. Remembering Gorbachev. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2022;82(4):503–511. doi: 10.1057/s11231-022-09375-6. [ DOI] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan, V. D., Akhtar, S., Dorn, R. M., Kafka, J. S., Kernberg, O. F., Olsson, P. A., Rogers, R. R. & Shanfield, S. (1998). Psychodynamics of leaders and decision-making. Mind and Human Interaction, 9, 129–181.

- Volkan VD, Ast G, Greer WF. The Third Reich in the Unconscious: transgenerational transmission and its consequences. Levittown, PA: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. [ Google Scholar]

- Volkan VD, Javakhishvili JD. Invasion of Ukraine: Observations on leader-followers’ relationships. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2022;82(2):189–209. doi: 10.1057/s11231-022-09349-8. [ DOI] [ PMC free article] [ PubMed] [ Google Scholar]

- Waelder R. Psychoanalysis and history. In: Wolman BB, editor. The psychoanalytic interpretation of history. New York: Basic Books; 1971. pp. 3–22. [ Google Scholar]